New book a decade in the making sets the tone for Hip Hop’s future

Scholars, artists and activists involved with UCLA’s Hip Hop Initiative are laying the groundwork for how Hip Hop will be understood 50 years from now.

The art form officially hits a half-century of influence in August 2023, with roots that can be traced back to a Bronx house party in 1973.

Meanwhile, “Freedom Moves: Hip Hop Knowledges, Pedagogies, and Futures,” published this year, is a book a decade in the making. It holds perspectives from Hip Hop artists and scholars who lend both joyful and critical lenses to the enduring power and influence of Hip Hop.

“One thing Hip Hop has been doing since day one, is organizing us, teaching us, moving us to do the right thing since day one,” said Samy Alim, director of Hip Hop Initiative and the David O. Sears presidential Endowed Chair in the social sciences UCLA. “And that has transferred all around the world so that Hip Hop becomes a soundtrack for marginalized people everywhere to do their thing, to fight back against oppression, or to fight the power, as Chuck D famously said in Public Enemy’s anthem.”

This book is meant to illustrate the impact of Hip Hop Culture over the last 50 years, but also to set an agenda for the next 50, he said. Alim also serves as associate director of UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies, which is home to the Hip Hop Initiative.

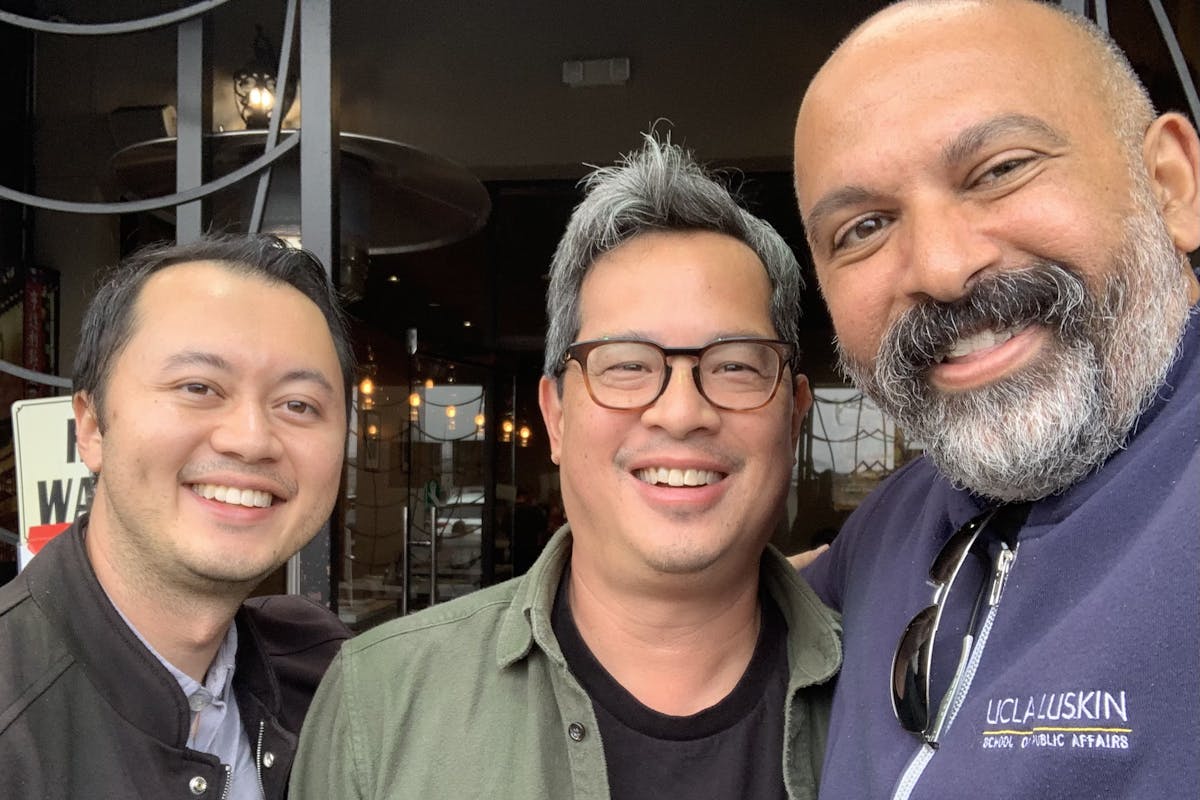

The series of essays that populate the book are derived from workshops and events organized by editors Alim, Jeff Chang and Casey Wong, many held at public-facing Hip Hop course held at Stanford University Institute for Diversity in the Arts. The language published in the book reads as it was spoken in those moments.

“Black Freedom culture is an oral culture and it’s very important that it’s captured as an oral culture,” said Wong, assistant professor in Georgia State University’s College of Education and Human Development. “That conversational component is in line with Hip Hop and who are we trying to speak to. Our goal was to make a book that’s deep enough for intellectuals at the university but that you can also read with middle school and high school students.”

There is intentional critique of the art form baked into the pages of “Freedom Moves. The editors intentionally held space held for voices not often heard in mainstream Hip Hop, such as queer and trans artists, indigenous artists and disability rights activists.

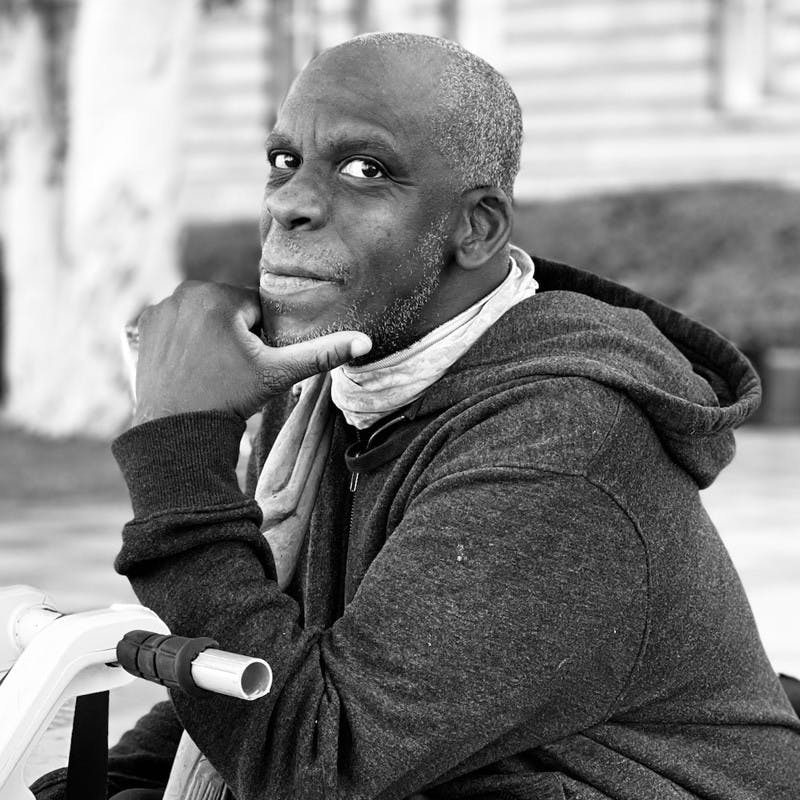

Two current UCLA PhD students in anthropology—LeRoy Moore and Stephanie Keeney Parks— want to inspire Hip Hop to make a home for fans and artists with disabilities.

Moore is the co-founder of Bay-area based global collective Krip Hop Nation with a mission to educate the industry and general public about the talents, history, rights and marketability of Hip Hop artists and other musicians with disabilities. Parks is mother to an autistic teenager whose love of Hip Hop creates both sense of belonging but also isolation.

Born with cerebral palsy, Moore has been a prolific journalist and organizer on behalf of a huge demographic of people who are largely excluded from the commercial trappings of the industry.

“One thing I’d like more people is to really see that black disabled Hip Hop artists and Hip Hop lovers have been there since day one,” Moore said. “I could tell you stories, I grew up in New York. I used to go out with my walker. I saw Hip Hop when Hip Hop was on the corner. I saw people on crutches, DJs that were women. I saw Hip Hop when Hip Hop was diverse, so I know it’s there.”

Early disability rights supporters in Hip Hop include Rob Da Noize Temple from Sugar Hill Gang. Moore himself is currently an Emmy winner thanks to his contributions the soundtrack of Netflix’s 202 Paralympics documentary “Rising Phoenix,” and a few mainstream artists are cracking open conversations around disability thanks to their own experiences as parents.

But ableism is alive and well in Hip Hop, Moore and Parks said.

“It’s hard to take Hip Hop seriously for example when they say things like ‘we’re fighting for communities and talking about our political world but then you don’t conceptualize disabled people as a part of it,” Parks said. “Disability is cross cultural. It affects everybody. Not having an eye on that is as serious as excluding women.”

It’s something Park witnesses often as she watches her 18-year-old son navigate the world. She’s working on her doctorate in anthropology, focusing on disability rights.

“Blackness and Hip Hop and language all come together for kids like mine who have a really hard time gaining access,” she said. “We deeply love this art form and in true African American fashion and style we do have to critique ourselves.”

The larger issue is that disability is not taken seriously as a political identity in any spaces, not just Hip Hop, Parks and Moore agreed.

“LeRoy and I are probably the least famous scholars in the book,” Parks said. “But we want to be seen as scholars on par with any other Hip Hop scholar, anyone focusing on those political identities that get taken more seriously. For Samy to agree with that and put us in the book means a lot.”

“Freedom Moves” is the third volume in the Hip Hop Studies series from the University of California Press, and the second linked specifically to UCLA, following last year’s release of “Rebel Speak: A Justice Movement Mixtape” by Bryonn Rolly Bain, professor in the World Arts and Cultures and African American Studies departments.

These are adding to a growing body of work that includes “Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation” by acclaimed author, historian and UCLA alum Jeff Chang, published by Picador.

Chang’s work with Alim and Wong started back in 2010 in developing the Hip Hop course at Stanford, drawing in community organizers from the area, and quickly expanding its focus.

“One thing we recognized was that by 2010, these kind of conversations had become a global thing,” he said. “You could go to any major city in the world and a lot of small ones and find young teachers and people literally studying Hip Hop as a pedagogy of the oppressed, or as Samy would call it, a culturally sustaining pedagogy.”

Chang hopes the book helps keep the dialogue about Hip Hop rich and flowing as more young people find their voices in the culture and within academia.

“We always have so much to learn from all these young folks,” he said. “All of the work we’ve done so far is a powerful that reminder that pedagogy goes two ways. It’s not about us being the teachers full of wisdom, it’s what’s happening in real life, in real time all around us.”

On April 13, “Freedom Moves” editors and fellow scholars will participate in an event in honor of the new book and the 50th anniversary of Hip Hop at the California African American Museum.